My art mentor, Ilene Satala, had a close connection to Frida Kahlo. She always spoke of her admiration for Frida’s honesty in her paintings. Her willingness to show her pain, joy and soul was a guiding force in how Ilene lived and created.

Ilene shared a powerful story, Saint Frida, she had written about her discovery of Frida. It is as follows.

“My connection to Frida Kahlo, the great Mexican woman painter, began almost by accident. People that know me know how passionately I feel about her and her work. I find I am often asked to give some kind of explanation about why I love her so much. This then is my sojourn to understanding her power and my own.

I take you on this journey not just to understand something of her life, but to open you to your own life. One cannot separate Frida from Mexico and the zest and spice that is the culture. As a North American westerner my cool, collected take on life melts under the heat of Mexican thinking.

As women, we need to free up our energy often trapped inside of us. To know Frida is to seek a path to find inner and outer freedom using life’s trials and difficulties where our pain is used as a fuel for liberation and joy is made all the sweeter from having tasted suffering. I write this to help you find your inner Frida and set you free as it has me.

Libraries before Google

When I was sixteen I was an aspiring artist. I realized on my own that I needed to find a hero as a role model for myself that could inspire me. I wanted to find a women artist that had become a great success in her lifetime – someone to read about and whose life I could learn from.

I adored my art teacher – all tall and elegant – and I asked him to help me on my quest. This, as primitive as it sounds, was before the internet and Google. To find out information you had to use a library and tons of books to find your way through lots of research.

I volunteered in the high school library and I had been methodically going through all the art books we had. We actually had many of them. They were all filled with artists that were brilliant, amazing men. I loved them all, don’t get me wrong. Michelangelo was compelling and Claude Monet filled my heart with blue water lilies and joy. Yet they were men and I was in a women’s body. What I wanted – no, what I needed – was a woman painter to point the way to me finding my own inner artist’s path of creativity.

My art teacher diligently searched his own personal library and came up with the American painter Mary Cassatt who had been befriended by the French impressionists. I liked her work of course and admired her sacrifices as an 18th-century woman painter. She painted images of women and children, but I just was not entirely satisfied. The pastel world of painted babies being bathed and ladies sitting in chairs was too placid for my sixteen-year-old mind that loved Twiggy and Jefferson Starship and granny glasses.

Was this it? Was this all, I asked? He was confounded and I knew he had done all that he could. His time was limited and he had given me Cassatt, however I was still hungry for more. I had to begin the hunt again.

Next I turned to the head librarian. She wore orthopedic shoes and lived with four cats and let her hair go grey. Underneath it all though she burned with the fire and power of knowledge. Books were her passion, her husband, and her lover. When I asked her what I was looking for she connected to me immediately. For weeks she toiled over trying to find books on women artists in history. It was not her field and she was dancing in the dark. Yet she danced for me in her search. It began to dawn on me how hard it was to find a recognized woman artist in 1966.

I will never know what contortions she went through but she produced one book borrowed on an inter-library loan and sent through the mail from the Library of Chicago. It was thick and it was on Latin American artists. It was 99% about male artists but one page stood out. In a large beautiful chapter on the work of muralist Diego Rivera, I saw a tiny footnote and one single image that took up a whole page made as a glossy color plate that they don’t do any more in books. The page held the picture of a woman staring out at me. The footnote next to it read simply that this image was a self-portrait of Diego’s wife, artist Frida Kahlo.

Well, I took a long look at her. She had big black eyes and she stared straight at me. No flinching, no pastel colors of Cassatt. Just dead-on looking down into my soul with eyes that burned bright. I felt pride and strength and courage in those eyes. Courage that I could feel as if she were a warrior radiating a determination that defied my senses.

I was chronically ill most of my childhood and thus there was something else in those eyes I recognized. Pain. The pain sickness brings on and fills your body up with. I too had dark eyes and I looked at her and saw something in me.

Her eyebrows were painted by her own hand as growing together creating her famous unibrow. It was too strange for me to understand why she did this. Her clothes reflected a culture I knew nothing about, but I liked her jewelry. She made me stop and look and feel and I knew she was important for me to meet this way. However I did not have a clue why.

I wanted to read more about her life and alas nothing more was said about her in the book. The librarian, feeling my need to fill myself up with women artists, continued her hunt. She looked for more about Frida, but had no luck. I had to be content that she had found a thin thread to give me. As time went on I forgot about Frida and almost gave up being an artist entirely. Yet, when I would see her again at the age of thirty I did at least know her name.

Finding Saint Frida

My husband and I had started a business of taking small groups of people on tours of ancient archeological ruins in Mexico, and then later into Honduras and Guatemala. To do this work we would do advance-scouting trips to new areas to check out where our next trip would be traveling. On this particular day, our guide had stopped at a weavers’ village for us to check out. It was on the way to other archeological ruins we were going to see. It seemed like a nice break from riding through the countryside and offered a chance to stretch our legs.

Because our guide understood that I was an artist, he thought I would respond to the people’s work in this village. He was right. I quickly fell in love with the town. And the artwork I saw was simply amazing.

It was a village of rug weavers that took wool and wove magic into them. They could create any picture you could imagine in those rugs. With tufts of beige wool they layered in color-dyed threads that formed ancient scenes and modern ideas. They had created a thriving international business for the whole village without the internet. They prospered and were a proud people.

As we slowly walked from home to home to look at the rugs they sold, we would often pass through living areas in the weavers’ houses to get to the workrooms. I observed that every house had a shrine table in the living space and a smaller separate one in the studios. They fascinated me as I could see they were very personal to each family.

I started taking longer looks at these altars. They usually were comprised of a table that had statues on them. There usually was the Madonna and often several other kinds of statues of Mary that I at the time did not understand. Jesus was there also, either on or off the cross, but present. Then pictures of family members in small frames decorated the surface. Locks of grandmothers’ hair were in tiny frames next to ancient brown photos. Pictures of children and grandchildren were aplenty.

Various saints were represented through holy cards and statues. Color was all around giving it a robust feeling. Candles glowed in votives in various kinds of glass holders, sometimes with colorful pictures on the sides of the glass of holy saints and sometimes plain ones. Adding to the mix were bright paper flowers as well as real flowers and dead flowers all on the same table surface. Then to top it off, tiny colored Christmas lights hung over the whole creation often blinking and adding an extra dimension of cheer.

It was festive and haphazard to my eye. Yet as I examined each altar I saw they had a real purposefulness to them. They were holy and filled with the personal and the divine. They were about family, love and sacred intent for the well-being of the family.

There was one picture that appeared on the altars from house to house – haunting self-portraits of Frida Kahlo. They were not always the same size or the same painting, but they were always present. I recognized her at once, the librarian’s face coming back to me as she opened that book of long ago to show me the prize of her search.

Frida’s face adorned the altars from one house to the next. Finally I couldn’t stand it anymore and I asked my guide why she appeared on these altars the families had built. He asked a woman weaver. I could see her collecting her thoughts. She answered with care and took some time to explain it to me. I waited patiently for the translation. She seemed to really be pouring her heart out. To my frustration our guide said “They got calendars one year and that is where the pictures came from.”

He stopped talking like that was it! The weaver had taken quite of bit of time to tell me the whole story of why Frida was appearing on the altars. Yet my guide reduced the whole conversation to one sentence. Over the days traveling with him and my husband, Conrad, I had gotten to know and respect him. I thought of him as a friend by now so I startled him when I forcefully asked him to take his time and really explain to me what the woman weaver had said.

I told him it was very important for me to know what this weaver really had to tell me. The weaver sensing my frustration with our interpreter stared fiercely at him also. Seeing we were both serious about this he switched gears and collected his thoughts. He asked her more questions. Then the story finally began to come out. What the woman said touched me deeply. It had greater implications than I knew at the time. It moved me and moves me still when I think about it.

The weaver said, “Frida is our saint” owning her personally with that statement. Pulling her arms inward to her heart, her breast.

“Like a saint she suffered in a broken body. She suffered because of her unfaithful husband. She suffered that she could have no children of her own. Her spine was broken when she was a girl and it never healed.

“Yet through all this pain she painted. She painted her life, her joy and her suffering. Like a saint, love burned in her. Life burned in her and she prevailed. She is one of our own – an artist and a woman. It doesn’t matter that the Church doesn’t acknowledge her as a saint. We know who she really is and we honor her by placing her on our altar.

“Like everyone on our altar, we ask for protection and love and good health for our family both living and dead. For the dead watch over us and their souls never die. I place corn meal on the table to feed my ancestors. Frida’s spirit is welcome at our altar and in our house and studio. Her artistic ways will help us in our weaving.”

Then she said again more passionately, hands flying, “Frida is our saint” and then loudly, “We love her.”

I vowed to myself right then to find out more about Frida and her life. I also wanted to understand the concept of saints.

So what is a Saint?

When I got back home I contacted several Catholic friends to give me the low down – Saints 101. As I was a former Lutheran we did not particularly go in for saints in general. They explained that there were saints that through just being so devoted and devoid of sin they were honored with the title.

Then there were the sinners that just lived on the dark side until they got the call. This conversion set them on a straight and holy path. Living in so much sin earlier only made them more powerful as a new dedicated follower of God.

Then there were the martyrs – those men and women who stood up to non-believers and paid with their lives. Often tormented and tortured they ultimately died rather than denouncing their faith. This ultimate sacrifice made them an excellent candidate for being a saint.

I started to get it why Frida was a popular saint for my weavers’ community in Mexico. She was all these things and more. Her suffering was acute and her joy ecstatic and blissful.

I learned that Frida’s husband was an atheist. So then Frida must have been this too, right? Yet she collected scared prayer tablets and hung hundreds in her house. She painted a famous work that shows her cradled in the arms of a Mexican goddess. The mysterious figure holding Frida is wearing a mask from Teotihuacán, an ancient sight known for worshipping a great goddess. The Sacred Feminine is shown suckling her breast. So what was really going on? Who was the atheist and who was the true believer?

Me Suckling by Frida Kahlo

If art was Frida’s faith, she was devout. If painting was her way of praying, she prayed constantly with reflection and power. She would not renounce her faith, her art, no matter what happened to her.

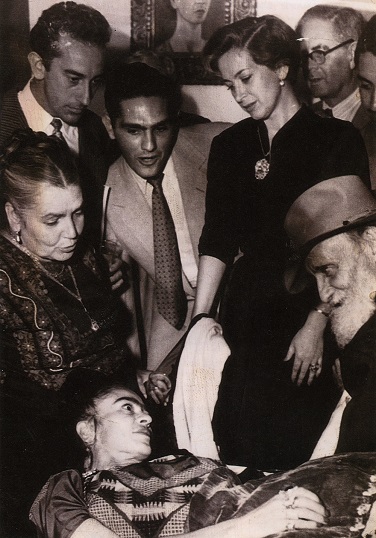

She lost her leg to an amputation at one point and had her spine operated on 30 times. Yet when her body was dying she had herself carried to a gallery dressed in her finery propped up in a bed to receive all her guest for her one women show. She laughed and drank and sang with everyone with great joy and happiness. She died in triumph – her spirit and her faith never destroyed but left burning brightly.

Frida with guests at her solo exhibition – 1953.

The Real Deal!

Shortly after I came home from Mexico I left again for L.A to visit a friend. She told me of a magnificent art show that was being held at the Los Angeles County Art Museum. The show was called simply ‘Mexico’ and it contained art from its ancient history to the present. We set out to see it and I loved connecting the masterpieces of the ancient world of the Maya and the Olmec and Teotihuacán.

I still had never seen an original of Frida’s work. I had no idea that any of her work was there in this show. I rounded a corner entering a large gallery where three paintings were hanging together.

I remember vividly first seeing a small painting of a deer with a woman’s head attached to the body. The dear was shot with arrows and a tear fell from the lovely women’s face. I spontaneously started to cry with tears running down my face. I couldn’t help it. I quite simply felt the woman’s pain for it still pulsed in the work. I felt Frida’s pain because the woman’s face attached to the deer’s body was that of Frida Kahlo.

The Wounded Deer by Frida Kahlo

I would learn later that Frida painted the wounded deer painting because she was in great physical pain. Her spine caused her great suffering because it had healed in a crooked pattern. That energy was put into the painting as a way of coping with it. Shortly after she painted it she meet a surgeon who greatly relieved her suffering for some time with a successful operation.

My response to this painting happened so spontaneously that I was shocked at my own behavior. I moved to the next painting. It was of Frida’s haunting face looking directly at me. Dark black monkeys clung to her neck and her black eye brows grew together. Her eyes were clear and dark and seem to look right into my soul. I was actually only a foot away from these canvases. I could not really believe it. At last I could see the real deal.

Self Portrait with Monkeys by Frida Kahlo

I stood back and looked at all three works. My emotions were running high. My Midwestern control had dissolved. I was vulnerable and open. I understood what the woman in the weavers’ village had been telling me. I also understood that Frida had put herself in her work.

Like a religious icon that is said to possess special powers, I felt the power in those paintings that could fill me with pain or with healing. I got one of my greatest gifts from her at that moment. I as a painter could also pour my energy into my artwork and make my paintings become alive.

This insight was my gift and I have used it ever since. For the first time ever, I had gone to a place I did not know I could reach through a work of art. Now I could do the same with my own artwork and the path was before me. I could infuse my work with life and meaning and move others that see it. Not just see it but feel it the way I had felt Frida’s life force in her work. I had finally found my inspiration of a woman artist that I had been looking for since I was sixteen.

I lingered looking and feeling reluctant to leave those pulsing paintings on the museum wall. I eventually left the physical building but that experience lingers in me even today.

A Saint’s Resurrection

I will leave you with one last Frida story. To understand it you must know something of a celebration held in Mexico on November 2 each year. It is called The Day of the Dead. The Mexican people take this day to prepare elaborate dishes of food, collect flowers and candles, and go out to the cemeteries.

The people decorate the graves of loved ones that have died making an altar of great color and beauty on top of the actual grave. It is thought that on this day the veil is especially thin and those whom we loved can be felt and communicated with once again.

The festivities include staying up all night communicating with your loved ones’ souls for they are not dead, of course, but living on the other side of the veil. It is a time to celebrate with sugar skeletons and humor and joy. It is a fiesta not about death, but about eternal life and how love never dies. Rather, it keeps us connected.

To my western mind I at first had difficulty understanding why something as serious as death was greeted with a festival. Then I gradually understood that this celebration day is all about the soul’s return and not about death, but rather love.

Frida died on July 13th (my Birthday) 1954 at the age of 47. When the funeral was over they took her body to be cremated in an open-air cemetery. Her body was placed in a furnace that had a window in it.

Many people had come to celebrate her life. To our Western minds it may feel morbid to watch the cremation, but it was the custom and felt very normal for them. Diego and the others stood watching in silence. As the fire was lit suddenly Frida’s body sat up, her eyes opened and her body glowed with intense light.

Everyone gasped and started saying “Is she alive?!” But no, she was not physically alive, yet she was filled with such intense light and energy that she glowed. Her spirit was vividly present giving everyone one last surprise before her soul left this earth. Everyone felt her spirit as being present one last time.

Reflecting on that story I ask you: Is this not the way a saint would die – gone in a blaze of light and fire, passion and bliss filling everyone in awe and wonder?

I add one more thought for you to consider. It is never too late for us to find our passion and what gives us bliss. Take your suffering that life gave you and use it to tell your story through creativity. If you’re holding back as I so often did before I met Frida, jump in! Find your voice and live. Let nothing hold you back. Really live your life to the fullest.

Make what you create infused with life and reveal the magic that is in your unique soul.

To Saint Frida I say, “Para Vida Frida.” You are my inspiration today and forever!”

~Ilene Satala